Why AMD's Spinoff Was Bad for Its Own Shareholders

[Opinion] Part II: Investigation shows that AMD's 2008 spin-off kept working against its own shareholders, year after year. Intel's board needs to take heed

Good Evening from Taipei,

AMD and Intel looked to have buried the hatchet last week with the announcement of an x86 Ecosystem Advisory Group. In plain speak, they’re working together to find new ways to use the x86 instruction-set architecture (ISA). An ISA is a set of standards for how processors operate. It specifies the way instructions written in software are translated into 1s & 0s so that chips can read, compute, and store information. The most famous alternative to x86 is the RISC architecture made ubiquitous by ARM.

The irony is not lost on anyone who saw Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger on stage shaking hands with AMD chief Lisa Su. We all know that these two companies are the Joker and Batman of computing. You can decide which is which.

In fact, I firmly believe that Intel is the single biggest factor which lead to AMD splitting design and manufacturing 16 years ago. Intel’s dominance — argued by the Federal Trade Commission to be anti-competitive — had a material impact on AMD’s marketing, operations and finances.

The flipside is that Intel provided more cash to its rival after AMD’s design-manufacturing split than AMD’s own counterpart ever did.

This is the story of how AMD’s investors lost out from that spinoff, with deleterious equity deals that hurt both AMD and its shareholders, costing them billions. It’s Part II of a two-part investigation into AMD’s 2008 spin-off of GlobalFoundries. In Part I, published earlier this month, I showed how AMD was shackled to its manufacturing partner, forcing it to lose both money and business.

In 2008 AMD was a distant (yet solid) second behind Intel in central processing units (CPU) and making gains in the graphics processor (GPU) market after buying ATI a few years prior. But the burden of running its own factories became too much, or so management thought, and they found a suitor. Funds affiliated with the Abu Dhabi government stepped in to take those fabs off AMD’s hands. The American chipmaker was to become fabless, and GlobalFoundries was born.

The split between design and manufacturing wasn’t quite a sweetheart deal for the Emiratis, but it did include sweeteners. The primary one was a long-term Wafer Supply Agreement, which proved restrictive and ultimately deleterious to AMD. I discussed this at length in Part I.

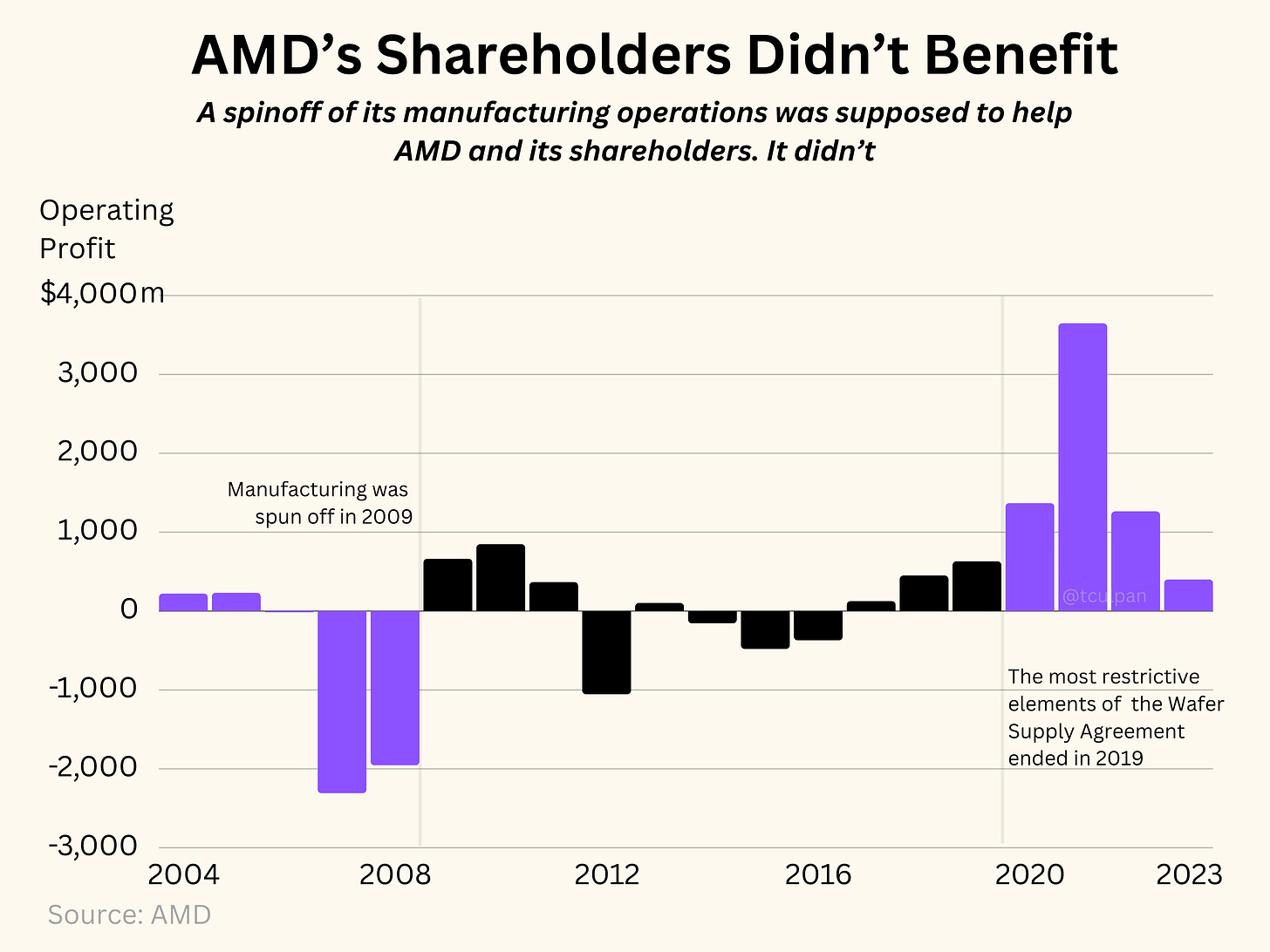

But at the same time as AMD was losing out year after year because of its contractual obligations, its shareholders were also getting a raw deal.

To be clear, I am not accusing Abu Dhabi’s Advanced Technology Investment Co. (ATIC) or affiliate Mubadala of doing anything illegal, nefarious, or wrong. In fact, their management team ought to be lauded for their business savvy in structuring this deal, and in negotiating hard in subsequent years. Conversely, in its 2008 10-K, AMD gave investors a sob story about what tragic things would happen if its deal with ATIC didn’t go through.1

Yet, a thorough investigation of the data shows that within just two years, AMD had foregone more than $6 billion in assets. Here’s how:

At the end of 2008, prior to the deal closing, its balance sheet showed $4.9 billion in factories plus $1.9 billion in property.2 By the end of 2010 property, plant and equipment stood at just $700 million. That’s a $6.1 billion drop in two years.

AMD also gave a 16% stake in itself as part of the deal, and issued warrants allowing ATIC to get 35 million more shares for free (well, at 0.1 cent per share) sometime over the next decade.3

In return, AMD got $700 million in cash, $1.1 billion in debt relief and a 34% stake in GlobalFoundries.4 Among the justifications for the terms of this deal were ATIC pumping its own money into GF, and taking on purchase commitments made by AMD. But the consummation of both was to the benefit of GlobalFoundries, not AMD.

Cross Holdings:

ATIC owned 16% of AMD

AMD owned 34% of GlobalFoundries

That said, it needn’t have been a terrible deal for AMD. A 34% stake in a new manufacturing business, GlobalFoundries, that’s funded by a generous benefactor could still be quite lucrative. Except, the worst was yet to come.

In 2010, a year after that first Wafer Supply Agreement was signed, the same group of Abu Dhabi investors bought Singapore-based foundry Chartered Semiconductor and merged it into GlobalFoundries. This was a brilliant move for Abu Dhabi, for GF, and for Chartered. But not for AMD.

In the process of GlobalFoundries’ expansion, and with the extra money put in by its controlling investor, AMD’s stake in GlobalFoundries went from 34% to 14%.

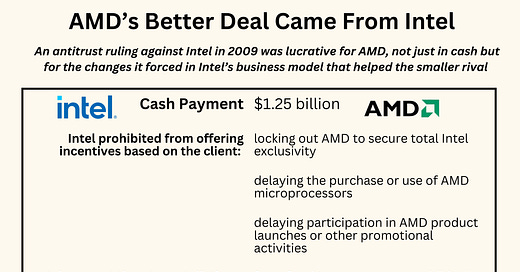

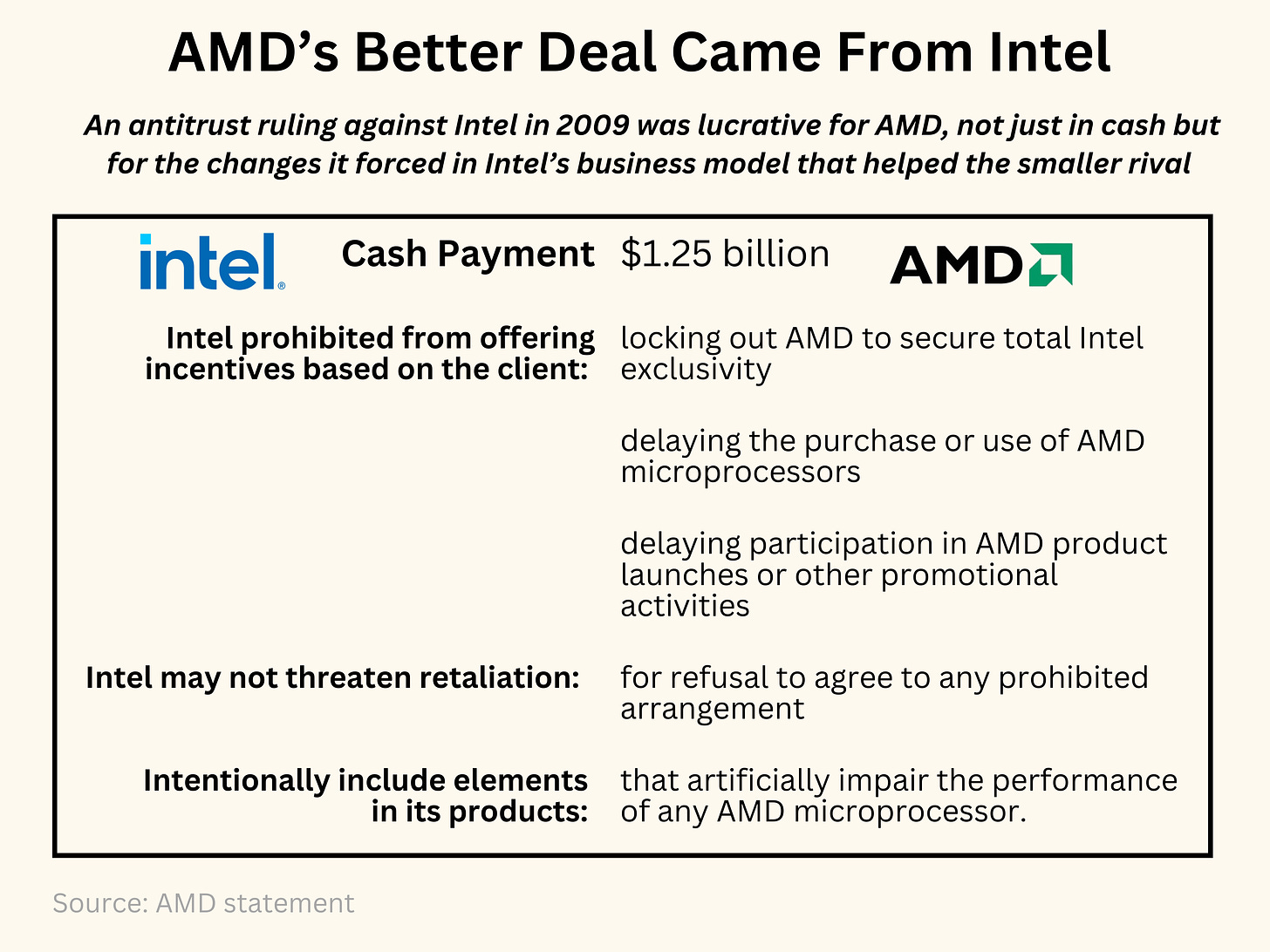

Remember, AMD only got $700 million in cash for the business which formed the foundation of GlobalFoundries.5 In fact, it made more from a 2009 settlement with Intel in which the larger competitor paid $1.25 billion and agreed to stop some of its most aggressive and damaging marketing practices. This was, of course, too little too late for AMD as it had already sold its factories and gone fabless.

Equity Lost

Things really got bad in March 2012. Desperate to ship product, and struggling with GlobalFoundries’ manufacturing issues, AMD needed to get a waiver on its exclusivity commitment. So it once again renegotiated the Wafer Supply Agreement (Amendment 2), and in the process made a highly consequential decision.

The $703 million AMD gave GF in 1Q 2012 to get that waiver — paying to not buy from GlobalFoundries — consisted of two parts. First was a $425 million cash payment. But the second part was the real killer: AMD gave up its remaining stake in GlobalFoundries, which it valued at just $278 million.

As a result, a little over three years after signing a landmark deal to hand over its semiconductor-fabrication plants, AMD was left with nothing. Yes, it got $700 million in cash and some debt forgiveness.6 But it didn’t get cheaper wafers, nor access to the world’s best manufacturing technology, and most importantly it no longer held a stake in a business that would IPO a decade later at a $26 billion valuation.

It’s important to remember that for AMD, GlobalFoundries’ profitability over the period between founding and IPO didn’t really matter that much.7 When a company IPOs, the only thing that matters is its public-market valuation and how much of it you own. Assuming no dilution, that initial 34% stake would have been worth $8.84 billion, even the watered-down amount of 14% would have been valued at $3.6 billion.

The pain didn’t stop with giving up its shares in GlobalFoundries.

A Single-Day $1.2 billion Hit

For five years ATIC sat on 35 million warrants — the right to buy shares. On 7 March 2014 it exercised them, giving ATIC another 4.6% of AMD for (next to) nothing. Not only was this dilutive to AMD’s shareholders, that transaction was valued at $138 million at the current share price but worth a whole lot more in subsequent years.

An even bigger hit was to come.

In 2016, a year in which AMD’s full-year revenue of $4.3 billion was 24% lower than a decade prior, it agreed to pay $100 million for another waiver under Amendment 6.

But the devil was in the details. Buried at the very bottom of that 21-page agreement: Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Development Co. was issued a warrant giving it the right to buy 75 million more shares in AMD at $5.98 apiece. That deal was recorded on AMD’s books at the time as a $240 million charge. Three years later, on 13 Feb 2019, AMD received $449 million in cash from Mubadala when the counterparty exercised the right to buy shares.

But even when AMD won, it lost. Those shares, equivalent to 6.9% of the company, closed at $22.85 apiece that day — making the stake worth $1.71 billion. In a single day, Mubadala made a $1.2 billion profit at other AMD shareholders’ expense.

The coda to this story, though, is that despite a massive loss in shareholder value, 2019 was probably the best year AMD had in a decade. It finally rid itself of the most restrictive covenants of that wafer supply agreement, and under new leader Lisa Su was on the cusp of tapping TSMC’s manufacturing prowess to ride the work-from-home boom and the AI explosion. You can read more about this in Part I.

Dear Intel: Make Chips, not Mistakes

Right now, Intel is expending a lot of energy trying to remain relevant. Sharing the stage with AMD as if they’re friends is one example. Intel’s Gelsinger complaining about US reliance on Taiwanese foundry TSMC is another. Both moves seem hypocritical. Gelsinger’s own company dropped the ball on manufacturing, and now provides “sizable business” to TSMC so that Intel can ship some of its most important processors.

AMD ought to serve as a lesson as Intel’s board considers its next move. It’ll be tempted to talk big and get a deal done quickly, but risks shortchanging shareholders in the long term. Over 15 years ago AMD found ways to justify its contract with ATIC, even having lawyers respond at length to an SEC query about the deal.

Back then, AMD’s board hid behind bankers, who submitted various comparisons and evaluations, to build a logical case to back up its decisions. You’d be hard pressed to claim that anyone was defrauded, or that any crimes were committed. I am certainly not doing so, and I am sure litigious lawyers would have filed suit quickly if they could rustle up an argument. Yet much of the damage done to AMD — the business — and to its shareholders, was done slowly, drip by drip, over more than a decade.

Both sides wanted a deal, and a deal is what they got. But American semiconductor manufacturing was further hollowed out. Less due to TSMC’s prowess, and more because of Intel. But now Intel wants to be friends with AMD to save its own bacon.

The US lost out not because GlobalFoundries’ primary shareholders are foreigners — GF, after all, is still an American company with US management — but because long-term interests of both the business and shareholders were put aside for a more-immediate need to get the deal done.

Intel’s future depends a lot on who its counterparties will be. In considering approval or not, US regulators and policymakers will need to understand the motivations of everyone involved — from highly-paid CEOs to status-chasing bankers.

Hand Up or Hand Out

And they’ll need to think twice about putting government money into the pot. There’s a huge difference between a hand up, and a handout. TSMC got a hand up when it was started under the watchful eye of the Taiwan government back in the 1980s, but has operated with almost complete independence ever since. Its leadership, particularly American-educated founder Morris Chang, had one focus as they built TSMC into the world’s most powerful company: the customer. It doesn’t feel like Intel is 100% focused on customers right now.

China’s SMIC, on the other hand, continues to get significant subsidies from its government and hasn’t made anywhere near the amount of headway Beijing would have hoped (despite the numerous reports of its supposed ascendence). SMIC’s management, like many compatriots, has but one master: the government. This isn’t a slight of SMIC, it’s a fact of doing business in China.

As key stakeholders consider the plight of Intel, they need to learn the lessons of AMD and decide what the long-term goals should really be. And as Washington draws up its Intel policy, it must decide if it wants to be more like Taipei, or more like Beijing.

Thanks for reading.

This included “buildings & leasehold improvements.”

Really! $0.001 per share.

This figure was a moving target. From 34% at announcement, the stake was at various points 23%, 16.7% and 14%, and then ….

There were some other, more complicated, equity and debt components to the deal. But in the main it was: cash, a stake in GF, taking on some AMD debt.

In addition to that $700m cash, AMD sold $125 of warrants to ATIC, allowing the latter to buy shares at a set (cheap) price. I don’t count this, and in reality this this is dilutive (bad) for AMD.

Depending on accounting treatment, you may need to recognize a loss on investments.