A $65 Billion Unprofitable Monopoly

[Opinion] America's most-advanced semiconductor fabs will remain underwater into the 2030s while remaining the only game in town.

Good Evening from Taipei,

This year’s two biggest tech stories will set the tone for 2025. The first is the continued rise of generative AI, and the escalating costs & challenges of building and delivering those models. The second is the struggles and doubts about the future of America’s pioneering chipmaker, Intel.

At the intersection of these two developments is TSMC. The Taiwanese company is the key enabler of AI through its advanced chip manufacturing, and the largest threat to Intel’s survival.1

TSMC’s problem is that it’s just too darn good.

Intel’s Pat Gelsinger spent much of his time as CEO taking veiled potshots at the independent chip foundry, hyping up the Hsinchu-based company’s risk to US national security while failing to offset the supposed danger by offering a credible alternative. Gelsinger’s remarks irked TSMC, which retaliated by cancelling a discount it was giving Intel to make the US company’s processors at its advanced 3-nm node, according to a riveting investigation published in October by Max Cherney and his colleagues at Reuters.

That move by TSMC around 2021 may come back to bite it. But it has a plan.

After decades trying to stay neutral both among clients and countries, TSMC is starting to understand that it’s now in the political crosshairs.

Being really good, with no credible competition is not a crime. Being a monopoly is. So TSMC this year started the task of making itself a non-monopoly. Instead of cutting its dominant market share, which is generally the first step in a regulator assessing monopoly power, TSMC redefined its market by enlarging it.

In this new depiction, which TSMC calls Foundry 2.0, the market now includes “packaging, testing, mask-making, and others, and all IDM excluding memory manufacturing.” In changing the paradigm, TSMC’s net addressable market suddenly doubles from $115 billion to $250 billion, which conveniently means its share drops from around 61% to 28%.2

Now, anyone who does non-memory chip fabrication is a rival. Not just pure-play foundries like UMC and GlobalFoundries, but integrated device manufacturers such as Intel. In addition, because TSMC has recently become a major player in advanced packaging, OSAT3 players — such as Taiwan’s ASE Holdings — get folded into the definition of TSMC competitors. That’s a pretty snazzy way to downplay your market dominance without actually amending your business model.

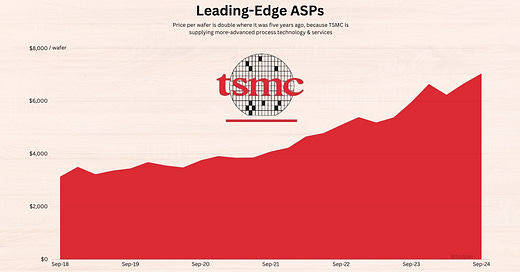

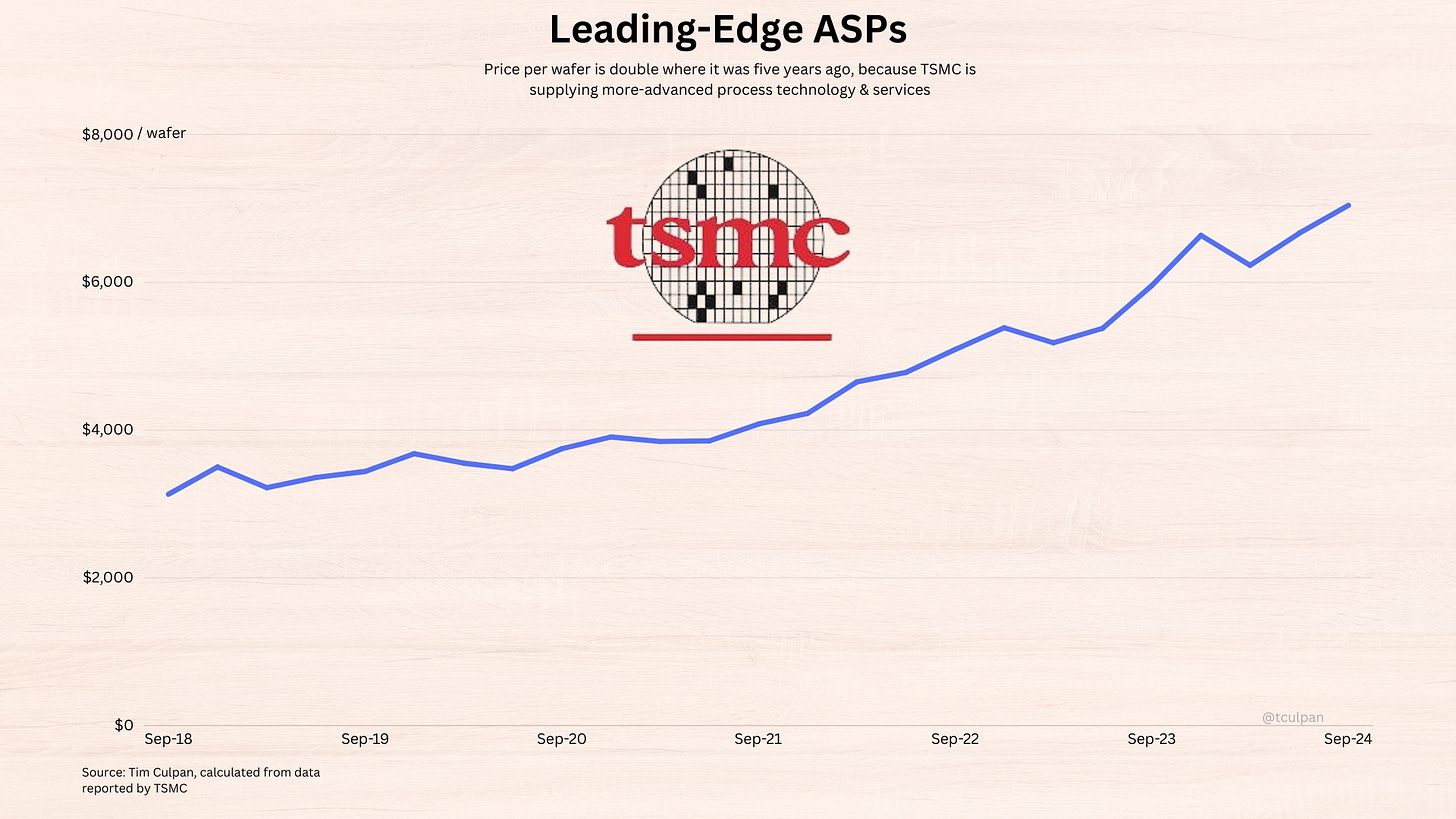

That move may not be enough. Being a monopoly isn’t only defined by market share. Pricing power is another criterion. TSMC has been raising prices over the past few years, although this doesn’t mean much because the cost of staying at the leading edge has also climbed.

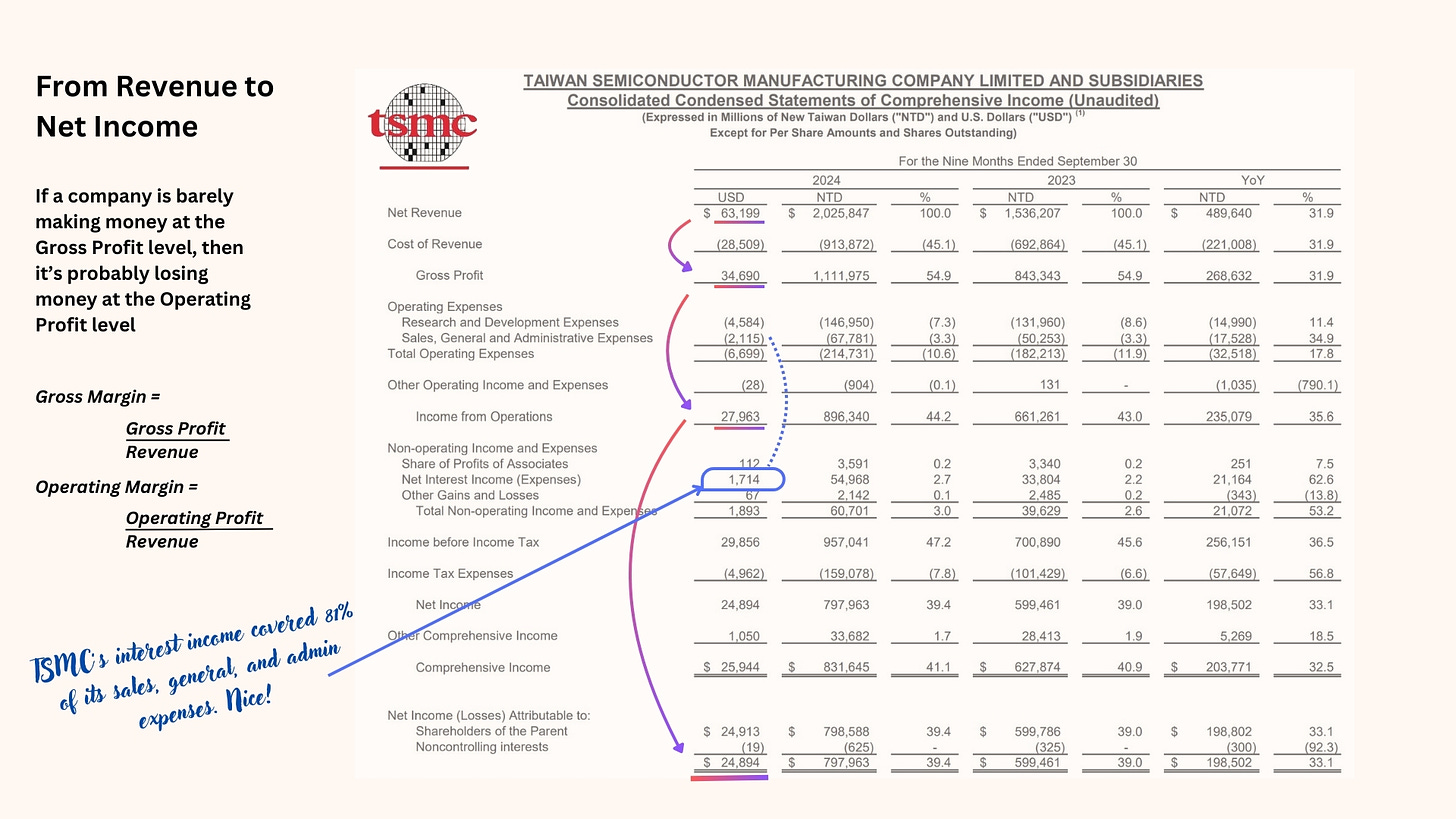

As a result, determining exactly what is a fair price for a wafer of leading-edge chips is tough, especially when there’s no other player in the market against which to compare. Gross margin, a measure of the markup against production costs, is a pretty good proxy. In that regard, TSMC hasn’t done itself any favors. Gross margins have floated above 53% in recent years, a level at which the company expects them to stay.4

US anti-monopoly law isn’t limited to looking only at actions happening within its borders. If overseas operations impact the competitive landscape domestically, then a company could still be a monopoly in America’s eyes. TSMC is now making advanced chips on US soil, and by mid-next year will count three of its biggest clients — Apple, AMD, and Nvidia — as customers of TSMC Arizona. That means it is operating in the US even if any supposed monopoly power is offshore.

TSMC’s solution: Lose money.

TSMC plans to invest over $65 billion on its US expansion, and we already know that Arizona is more expensive than Taiwan. To address this disparity, management has stated that it plans to charge customers more for US-made chips. If TSMC can strategically raise prices to offset the difference, yet limit that amount to ensure it’s still a little unprofitable, then it can ameliorate concerns that it’s a monopoly with dominant market share and pricing power.

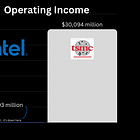

This is what TSMC may be doing. In recent investor calls, management has repeatedly said that overseas operations — which include Arizona and Kumamoto, Japan — will cut gross margin by 2% to 3% next year and into the future. TSMC is on track to make about $50 billion in gross profit this year from around $90 billion in revenue. Assuming a moderate 5% rate of revenue growth next year, overseas operations will suppress gross profit by around $2.5 billion.

Sunny Lin, an analyst at UBS, ran the numbers. She calculates that gross margin, and thus gross profit, at its offshore locations could be close to zero. Management kind of confirmed this analysis when Lin posed the idea at TSMC’s last IR call in October, agreeing that profitability is much lower but not confirming (nor denying) that these fabs are actually unprofitable.

Let’s recap how revenue flows through to net income: Revenue less COGS5 → gross profit, less operating costs → operating profit, less(plus) non-op items → net income. If Arizona is running at close to zero gross profit, then it’s almost certainly unprofitable at the operating level.

Under TSMC’s business model, new fabs start off less profitable and then enjoy fatter margins as they mature. TSMC’s first Arizona fab will lose money for a few years, then turn profitable, but by then a new fab will come online and drag down P&L again. Hence the company predicting a 2-3 ppt hit to gross margin for a few years.

With Arizona’s cadence of new fabs — scaling up in 2025, 2028 and 2030 — TSMC’s leading-edge US capacity will lose money into the next decade.6

Should Intel Foundry nail its coming nodes — 18A and 14A — then TSMC might have meaningful competition in advanced manufacturing, which would likely mean price competition and a further erosion of US margins.

That would be great for TSMC, because it could make the case that it’s not a monopoly while still controlling the broader foundry market.

The more likely scenario is that Intel doesn’t pose any real risk to TSMC Arizona, but the American company keeps pressing the point that advanced chips need to be made on US soil for national security reasons.

That would also suit TSMC just fine, because in doing so Intel would narrow the definition of “market” from all chips made at advanced nodes globally to only those “made in the US.” And since TSMC Arizona might still lose money, we may find ourselves with the absurd situation where a $65 billion unprofitable business is actually a monopoly.

I look forward to watching US political leaders wrap their heads around that.

Thanks for reading.

This is my last piece for the year. I’m taking book leave for a few weeks and will return in the new year. Thanks for your continued support these past few months. And if you’re new to my work, do subscribe. I publish Wednesdays (analysis) and Fridays (chart), with exclusive news when it happens. My work is independent, and I don’t do press-release journalism. What you read here cannot be found anywhere else.

If you followed my work this year, you’d have been the first to learn:

Apple Chips Are Now Made in the US by TSMC

AMD Will Fab HPC Chips at TSMC Arizona Next Year

Foxconn Executives (at Apple BU) Were Arrested for Bribery in China

AMD is Not the Model for Intel to Follow, and Why

Nvidia’s Blackwell Hiccups Were Overcome, and On Time

The Death of LCDs Means New Life for Chips

Most Popular Posts of 2024

Although, it could be argued that the biggest threat to Intel is Intel.

This is based on the size of the market in 2023, according to TSMC.

OSAT is an old-school abbreviation for Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly & Test.

Albeit lower than the heady Covid days when they pushed 60%.

Cost of Goods Sold.

The older fabs, eg. the one launching in 2024, might be profitable by, say 2030, but it will no longer be leading-edge.

All new leading edge fabs lose money in the beginning though, but through the magic of depreciation profits become fat during the trailing edge years (decades).