AMD Split Shackled Chipmaker for a Decade, Investigation Shows

[Opinion] Part I: A lesson for Intel - restrictive & secretive covenants inked during AMD's 2008 spin-off hurt the chipmaker, costing it billions of dollars and lost business

Good Evening from Taipei,

A new investigation across more than a thousand pages of documents including earnings reports, securities filings and wafer contracts shows the true nature of AMD’s 2008 split between design and manufacturing.

That deal resulted in one of America’s most respected chipmakers being weighed down for more than a decade by its relationship with its former manufacturing division, GlobalFoundries Inc., costing it billions of dollars and an untold amount of business.

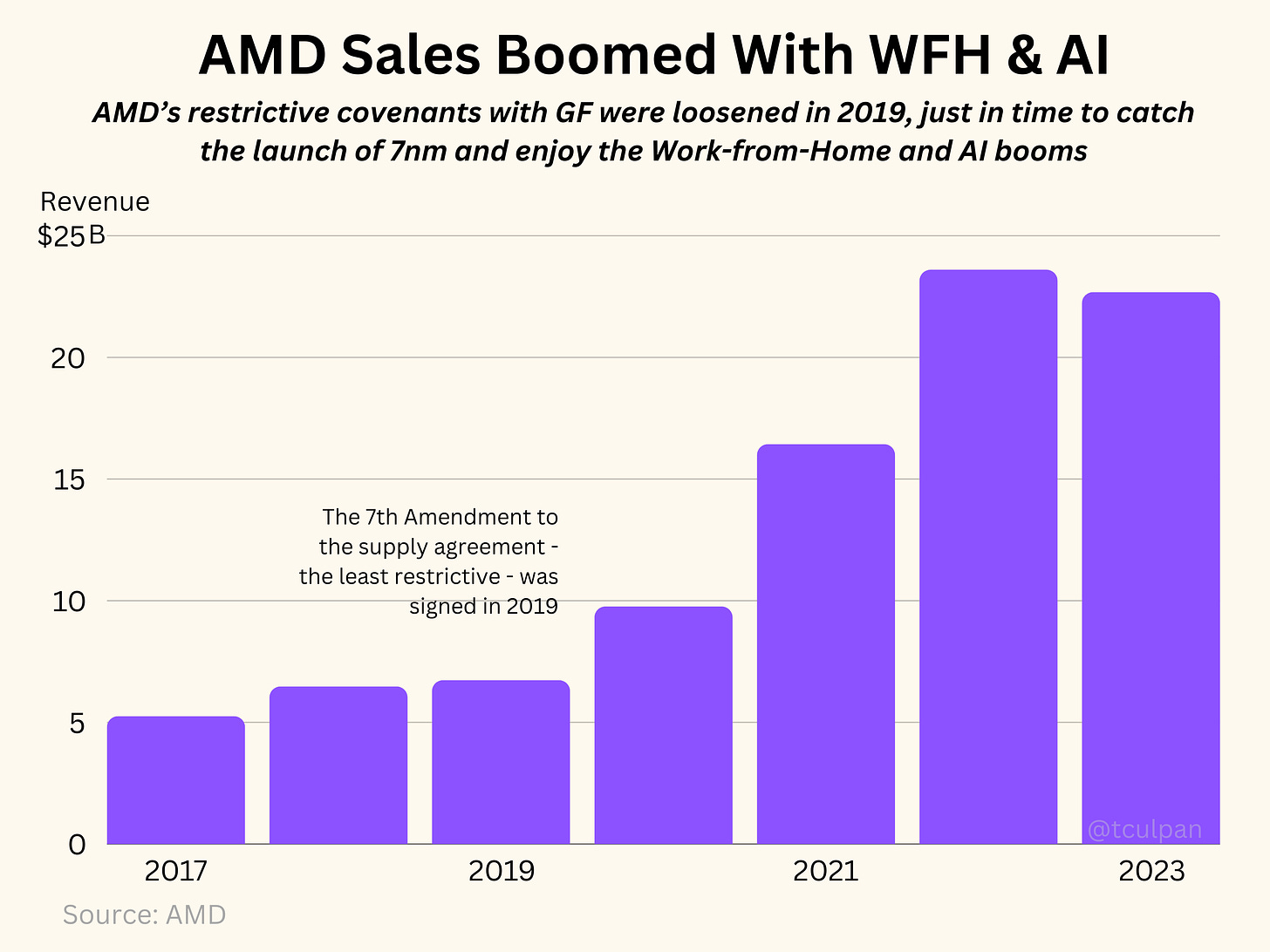

Once the shackles were released in 2019, however, revenue and earnings shot up: just in time to ride a Covid-related surge in chip demand and then the AI boom which drives its business today.

The lessons learnt from AMD serve as a warning to Intel executives, board members, shareholders, would-be buyers and policymakers. This story also shows why the US is unlikely to catch Asian foundries, no matter how much money federal and local governments throw around.

This is Part I of a two-part investigation into AMD’s 2008 spin-off of GlobalFoundries. In this Part, I show how AMD was shackled to its manufacturing partner, forcing it to lose both money and business. Part II will look at the deleterious equity deals that hurt both AMD and its shareholders.

“A Landmark Day”

For more than a quarter century, Intel and AMD dueled over the market for computer processors. Intel was well ahead, and AMD was a worthy competitor. A 2006 deal to buy ATI put it in league with Nvidia in the increasingly lucrative market for graphics processors (GPUs).

But a few slip ups on the product side left AMD struggling. With the burden of having to pay for factories, whether or not they were producing quality chips, the financials started to weaken. AMD posted an operating loss in three out of five years before making its dramatic move.

It was sixteen years ago next week (7 Oct 2008) that AMD announced the sale of its factories to companies connected to the Abu Dhabi government. The Foundry Co. was born, later becoming GlobalFoundries Inc. And AMD, rejecting the Real Men Have Fabs trope, became fabless.

“Today is a landmark day for AMD, creating a financially stronger company with a tightened focus,” president and CEO, Dirk Meyer announced. “It really changes the financial model around how we pay for leading-edge semiconductor technology.”

AMD only got $700 million in cash out of the transaction, plus a 34% share in The Foundry Co. (Most of the money put up by ATIC went directly into the new company, not to AMD).

Nevertheless, sell-side analysts loved the idea. And after a brief dive, shares rallied over the next two years.

CEO Dirk Meyer was only half right. Becoming a fabless chipmaker alongside pioneers like Qualcomm and Nvidia did change the financial model. What it did not do was create a financially stronger company.

Superficially, and in the short-term, things appeared good. AMD returned to operating profit in 2009 and stayed in the black for three years. It didn’t last.

In reality, what should have been a good deal for AMD and its shareholders — dumping expensive fabs — was almost entirely poisoned by obscure and restrictive contracts management signed with the counterparty to the trade.

I want to make clear: I don’t blame or accuse AMD’s counterpart, the Abu Dhabi government and its funds, of anything. They negotiated a good deal for themselves and committed billions of dollars to give GF a chance to remain at the cutting edge. Their savvy deserves recognition.

Prior to selling its facilities, AMD not only made chips at its own factories but outsourced some products to third-party foundries including UMC, TSMC and Chartered Semiconductor. But a Wafer Supply Agreement signed as part of the sale of the fabs meant that AMD was contractually obliged to “purchase substantially all of our microprocessor products from The Foundry Company.” (In this parlance, microprocessors meant CPUs). That deal was to be in effect for as long as 15 years, terminating no later than February 2024.

AMD’s 32nm handcuffs

Right from the beginning, AMD shackled itself to its primary supplier for a technology that didn’t yet exist. At the time, 2008, AMD was established at the 65nm node and transitioning to 45nm. By comparison, Taiwan’s UMC was also on 65nm and TSMC was working toward volume production at 40nm while preparing to tape out SRAM at 28nm.1 GF was also chasing 40nm, and after that would come 32nm but not for another two years.2

“Once The Foundry Company establishes a 32-nanometer qualified process,” AMD wrote in its filing for 2008 (published in 2009), the chip designer would purchase from this one supplier “specified percentages of our GPU requirements, which percentage is expected to increase over a five-year period.” (emphasis added).

In a nutshell, the Wafer Supply Agreement (2 March 2009) spelt out AMD’s obligations to buy from GlobalFoundries:

all of its CPUs (called microprocessors)

priced on a cost-plus basis (confidential)

an increasing proportion of its GPUs, once 32nm was delivered.

It was a bad deal, but clearly AMD needed to offer something in order to get its new investors to sign on.

More-expensive Wafers

Not only was it bound to GlobalFoundries for substantially all of its CPU capacity, AMD’s pricing deal also meant that it would pay more for wafers made at GF than if it were to actually make them inhouse. That’s right, I am not making this up. Instead of getting cheaper supply by offloading its costly fabs, the fabless chip designer had a more expensive cost base.

“We compensate GF on a cost plus-basis, which results in increased per unit manufacturing costs for AMD compared to manufacturing wafers in-house,” AMD wrote in its 10-K for 2009.

Variable costs like materials and labor are only a fraction of the expense of making a chip. If demand falls, you can buy less chemicals and hire fewer people, but the impact from doing so is minimal.

Instead, depreciation of the factory and equipment are the primary component. These costs are spread out over the total amount of product made. That means, perversely, if output falls then the cost per unit actually increases. And since AMD was signed up to pay for wafers on a cost-plus basis, then decreasing orders — or GF being unable to hit both yield and scale — would drive the price higher. A primary reason why TSMC enjoys the fattest margins in the sector, despite purchasing the most expensive equipment, is because it scales quickly while achieving high yields.

Again, AMD spelt out the implications of its purchasing deal: “The under-utilization of GF manufacturing facilities may increase our per unit costs and may have a material adverse effect on us.”

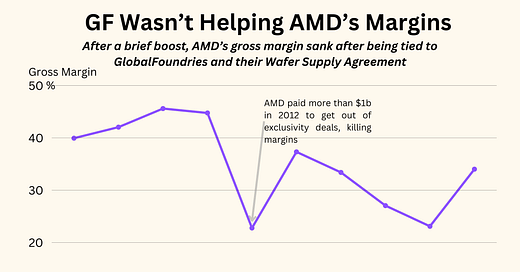

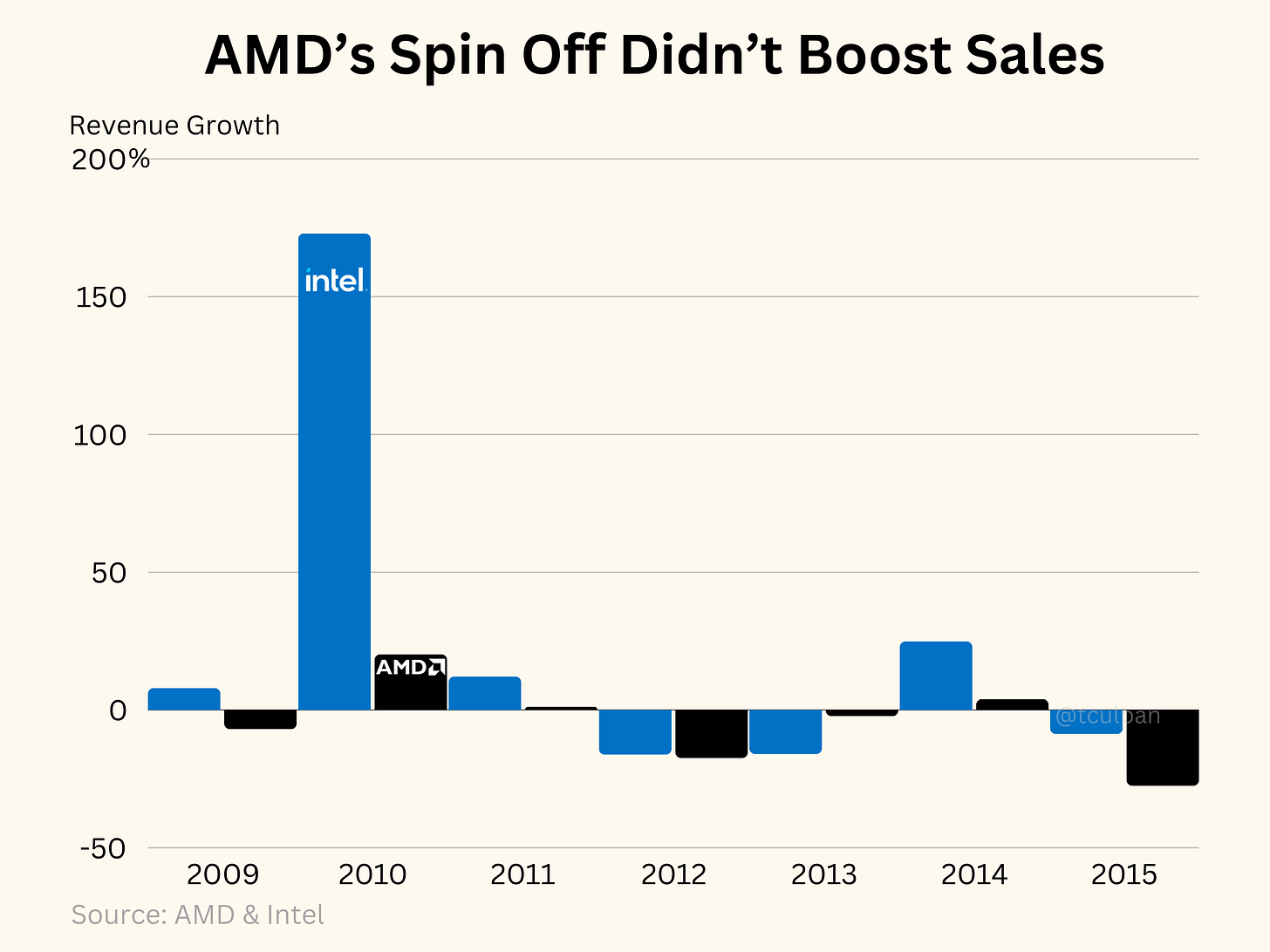

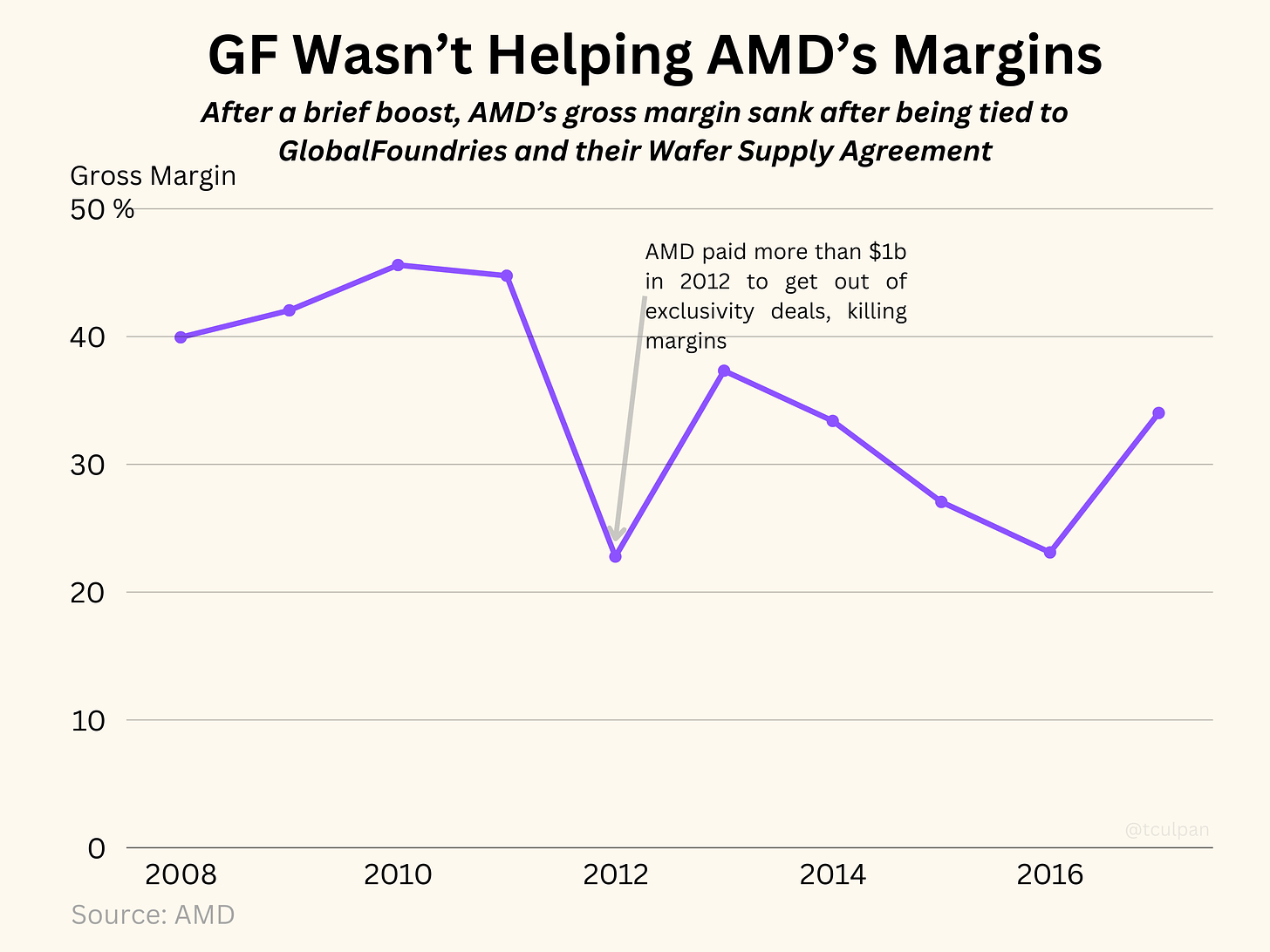

Although profit margins got a brief boost in the few years immediately following the split, it soon became apparent that the deal was not geared in AMD’s favor but toward the buyer of the factories. In reality, much of that short-term turnaround in AMD’s fortunes came from macro factors as the world emerged from the 2009 global financial crisis — evidenced by strong revenue growth at Intel and elsewhere in the chip sector.

A subsequent slump in gross and operating margins, including four operating losses within five years, showed that the new fabless approach wasn’t a winning strategy for as long as AMD was tied to a manufacturer with restrictive terms. Even more so if that supplier couldn’t keep up in the technology race.

Let’s Deal Again

In 2010, for example, AMD pushed back the release of its Llano processor by a year because GF couldn’t get its 32nm node up and running on time. That served as a catalyst to rewrite the Wafer Supply Agreement (Amendment 1) in March 2011. Instead of being tied to buying substantially all of its processors and an increasing number of its GPUs from GF, AMD instead committed to buying a set amount of wafers at 45nm and 32nm, and paying based on both yields and the number of good die delivered.

That was a much better deal for AMD — restrictions were loosened, and it was even given latitude to “work with other foundry partners to design and prepare to manufacture GPU Products.” But it was still tied to minimum purchases, and gratuitously agreed to pay $430 million in bonuses to GF during 2012 for actually hitting its targets. All up, AMD was on the hook for up to $3.4 billion in purchases from GF in 2011 and 2012 — compared to $3.5 billion in Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) in 2010.

Despite the commitments and bonuses AMD offered it, GF still couldn’t deliver in 2012. (Shareholders even filed a lawsuit against AMD over the Llano delay). The situation was so dire that AMD renegotiated the WSA again (Amendment 2) and paid $703 million in 1Q 2012 alone just to get out of that exclusivity arrangement and head to a foundry that could deliver (TSMC). Jon Y at Asianometry has a great video on this saga from the TSMC perspective.

By the end of 2012, AMD was still desperate and rushed to rewrite the purchase agreement once more (Amendment 3) in return for paying another $320 million just to, once again, get out of the exclusivity deal.

But here’s the thing about that second and third amendment (March & Dec 2012), they only gave AMD a temporary waiver. Section 1 of this third revision had AMD clearly stating it will continue to remain exclusive to GF (aka FoundryCo), despite the fact that these get-out-of jail cards were getting expensive.

The more than $1 billion in charges — not to mention inability to ship product on time — had slashed AMD’s 2012 gross margin by more than 22 percentage points (that’s huuuge), and plunged the fabless chip designer into a full-year operating loss instead of what would likely have been a moderate profit. (And five years later, it paid $30 million to settle that shareholder lawsuit).

By March 2014, five years after the first Wafer Supply Agreement was inked, both sides weren’t even pretending that their marriage was working. The Fourth Amendment stated:

“The Parties acknowledge that the tape out of the [****] Product with FoundryCo as required by Section 1 of and Exhibit A to the Third Amendment has not occurred.”

GlobalFoundries was magnanimous enough to let AMD out of that exclusivity deal (seemingly for free), but only on the condition that AMD sign on to be the exclusive partner for another product.

Another two amendments were negotiated, each offering AMD a little more slack but keeping the collar firmly attached nevertheless, and with commitments to purchase a certain amount of capacity from GF. Among them was Amendment 6, signed in August 2016, which had them agree to “work in a spirit of partnership and good faith to focus resources to assist FoundryCo to develop its 7nm process technology.”

The Great Escape

AMD’s seventh and final amendment3 to the Wafer Supply Agreement was the one which finally gave it freedom.

Signed in January 2019, the chip designer still had procurement agreements with GlobalFoundries, but they were almost without restriction when it came to what truly mattered to AMD. In fact, long-term supply deals are common between designers and foundries, and serve as a way to ensure predictability and stability as companies like TSMC and UMC plan billions of dollars in annual expenditure.

“AMD may at any time tape out products of any type with and procure foundry manufacturing services from any other foundry with respect to any and all products at the 7nm and subsequent Process Nodes (e.g. 5nm, 3nm) without any obligation or liability of any kind to FoundryCo as a result,” Amendment 7 stated.

Note that this freedom specifically pertains to 7nm and beyond. But note also that it was barely two years earlier that the two had agreed to work together to help GlobalFoundries develop 7nm. The reason was simple: GF had killed its 7nm plans, and TSMC had pushed them into doing so.

When GlobalFoundries was established in 2009, TSMC was not the outright victor. It hadn’t yet caught Intel and was even struggling with its 40nm process. AMD itself was impacted by this issue, according to reports at the time. So there didn’t seem to be a lot of risk in relying on the very factories it had just spun out, especially since the new investor was putting in fresh cash to expand capacity and technology.

But TSMC did solve those problems and Intel fumbled, allowing the Taiwanese foundry to catch up on manufacturing technology. AMD’s nearest rival in graphics, Nvidia, had always leant heavily on TSMC. Their founders Morris Chang and Jensen Huang were old friends, and the graphics-chip designer was not only developing great GPUs but getting access to the best fabs in the world.

For AMD, the saga of 32nm couldn’t be repeated. And with Intel falling behind, AMD’s new chief Lisa Su saw an opportunity to make gains in CPUs, if only she could actually tap into TSMC’s superior manufacturing capacity.

So while AMD had agreed to work with GlobalFoundries on 7nm, that meant mastering a very difficult and expensive new set of tools: EUV. By July 2018 TSMC had 7nm in volume production, with the EUV version 7nm+ expected by year end.4

GlobalFoundries, meanwhile, probably knew it couldn’t master EUV and used the excuse that most customers didn’t need 7nm anyway as a cover to pull the plug. It was, of course, wrong. AMD needed it, Nvidia needed it, and soon Intel would be needing it. Under Pat Gelsinger, Intel The Chip Designer would turn to TSMC’s 7nm to make its Meteor Lake processors because Intel The Chip Manufacturer couldn’t manage it in time.

Enabled by this switch to TSMC, and no longer weighed down by the albatross of GF hanging around its neck, AMD’s revenues jumped 45% in 2020, and another 68% in 2021. The key driver of that growth was the company’s non computing & graphics segment, which at the time it called enterprise, embedded and semi-custom.

Covid-driven work-from-home, coupled with streaming, online shopping, and a broad shift to the cloud proved a boom for AMD at just the right time. In earnings releases and investor calls, AMD was trumpeting Microsoft, Google and AWS as cloud-service providers that had switch to its high-performance chips. It would never have been able to develop or build these chips had it still been tied to GlobalFoundries’ lagging technology.

Today’s AMD is … Intel

Intel today is AMD circa 2008. It does have good products and pretty good manufacturing. Like AMD back then, it’s not a long way behind on technology nodes, and there’s still a chance it’ll catch up. In 2008, Intel was AMD’s nemesis. Today, TSMC is Intel’s nemesis.

Put simply, Intel isn’t the best chip manufacturer anymore, and you cannot be among the best chip designers if you don’t have the best production technology. Apple, Nvidia, AMD, Qualcomm, Broadcom (and until recently Huawei) are all able to remain at the very forefront of semiconductor devices because they can tap TSMC. Even Intel is turning to TSMC to stay in the race.

There’s a good chance Intel will follow the same path as AMD, becoming Intel Design and Intel Foundry Services. This isn’t the only way for the chipmaker to proceed: it could sell off specific product groups, merge with other companies, go private, or a combination of these. But at this stage, Design + Foundry seems the most logical route.

Yet the big trap Intel could fall into is to do some kind of spin off deal that requires Intel Design to buy from Intel Foundry. Doing so might sweeten the pot a little, and perhaps even attract US government support. But this would necessarily limit Design’s flexibility to offer the best chips, and as the AMD-GF saga shows, wouldn’t guaranteed Intel Foundry stays in the lead anyway. The US limiting Huawei’s access to TSMC proves the point: The Chinese giant is forced to buy from an inferior foundry (SMIC) and has suffered as a result (despite claims that the Shanghai-based foundry has pulled a rabbit out of the hat to close the gap).

The story of GlobalFoundries also serves as a warning to US policymakers. Throwing money at a manufacturer doesn’t guarantee technology leadership. GlobalFoundries was not short of resources or cash. ATIC and Mubadala were generous, and they were committed to ensuring GF stays in the race. But money doesn’t solve all problems. Chinese policy makers also know this, having spent what I estimate to be at least $500 billion over the past 25 years, but still failing to catch up.

If Intel Design is to survive, it needs access to TSMC. And if Intel Foundry is to survive, it needs to prove it can be (almost) as good as TSMC. That cannot happen if the two remain contractually, and sentimentally, connected.

Thanks for reading.

In Part II, I investigate the non-operating side of the AMD spin-off deal, specifically the transaction’s structure and equity agreements which meant AMD shareholders lost out when they should have gained. Make sure you’ve subscribed.

This was not TSMC’s finest hour: 40nm had troubles.

40nm and 28nm were considered by AMD to be half nodes.

Probably best to say “most-recent” as they could, in theory make more tweaks.

7nm+ aka 7N+ and 7nm FinFET plus.

So the lesson isn't that going fabless is bad but rather that, if you do decide to go fabless, make sure to sign a deal that lets you compete properly afterwards!